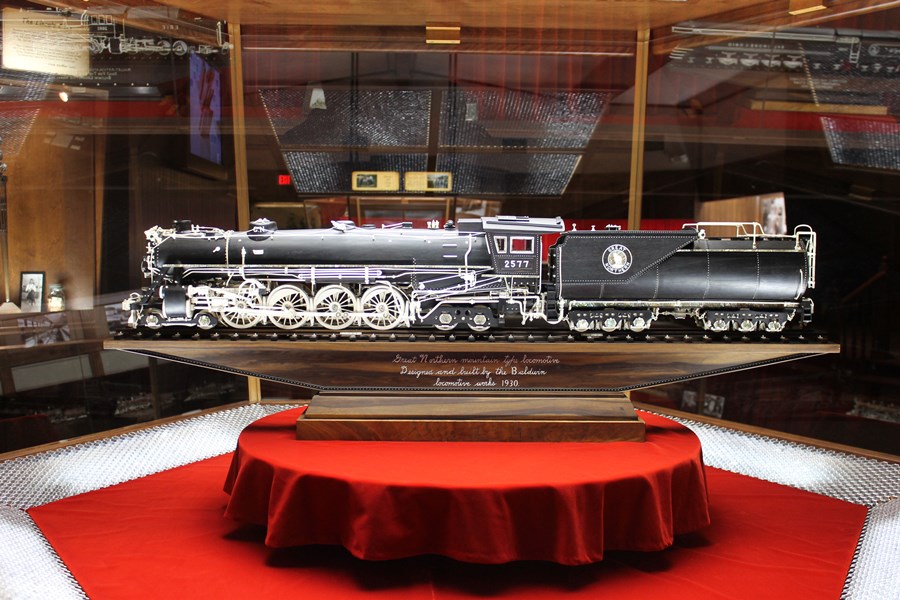

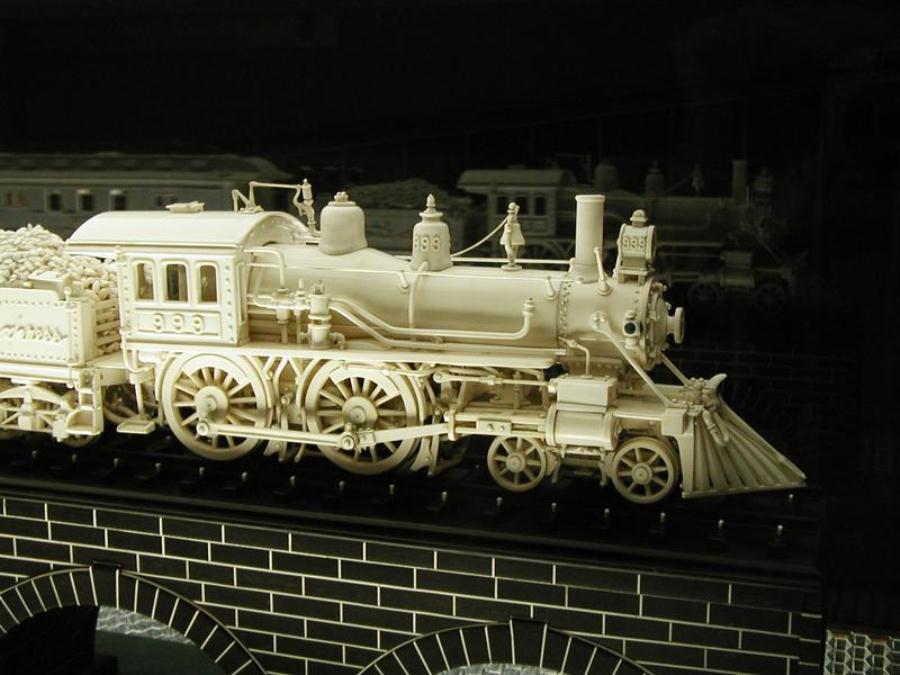

Hand-carved, Great Northern steam engine—Ernest Warther considered this his finest work.

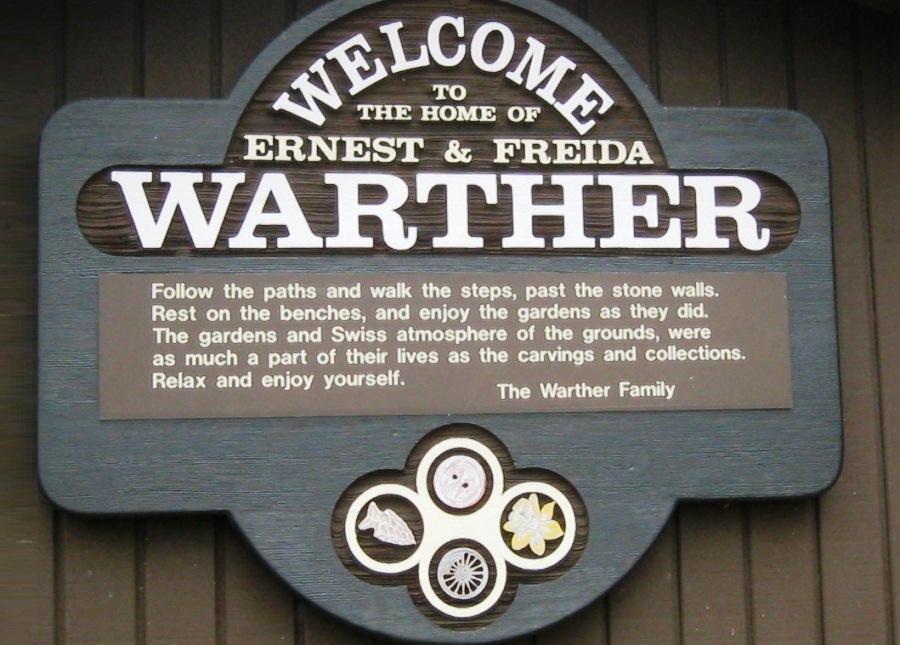

Sometimes the most amazing treasures can be found right in your own backyard. Case in point . . . the Warther Museum in Dover, Ohio is one of those one-tank trips that, for us, is so easy to take and so easy to miss if you’re not looking for it.

330 Karl Avenue

Dover, Ohio 44622

(330) 343-7513

Open 7 days a week

9AM – 5PM / Last tour starts 3:45PM

website | facebook | instagram

Family-owned and operated, the museum is home to Ernest Warther’s stunning miniature replicas of steam engines that Warther hand carved from walnut, ebony, and ivory.

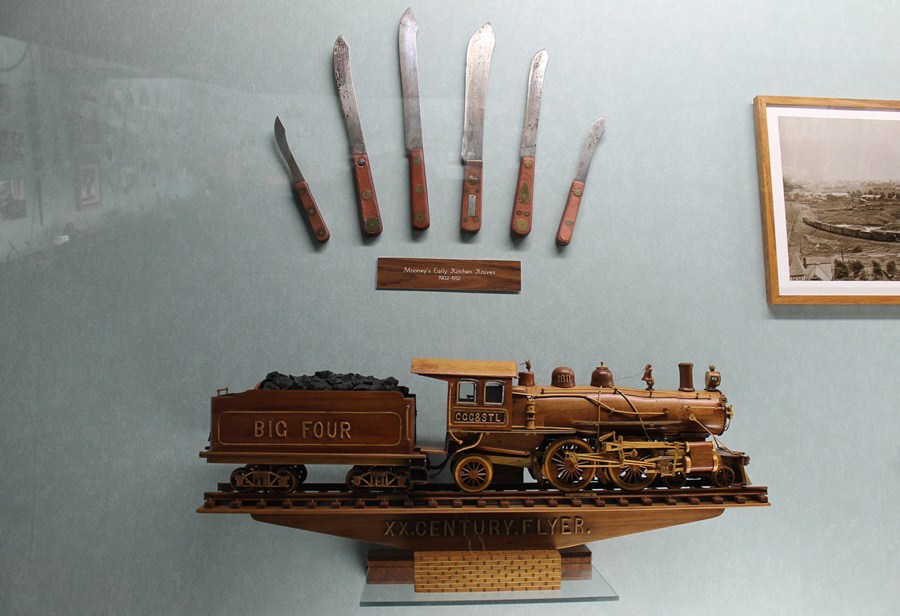

It also houses Warther’s extensive collection of arrowheads, handmade knives, and signature wooden pliers.

If you love trains, you will love this!

Though he received handsome offers for his work, Warther chose not to sell anything. Instead, he made kitchen cutlery to support his family and continued carving as a hobby. He and his wife, Freida, were content to live in their little house with their five children and lead a simple life.

Ernest “Mooney” Warther was born in 1885. At age five, he met a hobo who showed him how to carve a working pair of pliers out of a single block of wood with just ten simple cuts. That day triggered Warther’s 79-year passion for carving. Read more

Ernest “Mooney” Warther was born in 1885. At age five, he met a hobo who showed him how to carve a working pair of pliers out of a single block of wood with just ten simple cuts. That day triggered Warther’s 79-year passion for carving. Read moreA Visit to the Ernest Warther Museum & Gardens

We didn’t know what to expect.

We were on our way home from a long weekend in nearby Walnut Creek, and we knew there was a train museum in Dover. Sounded interesting, but we had never heard of Ernest Warther—have you?—and sometimes small, obscure museums turn out to be nothing more than rooms filled with memorabilia that are of no interest to anyone but the immediate family. That’s not the case here.

On the front left of the building is a super-sized version of Ernest Warther’s signature wooden pliers. Warther made thousands of wooden pliers that were so popular they became his calling card. The wooden pliers on the building form a perfect W for Warther.

The Warther Museum sits atop a hill in Dover, Ohio at the edge of town. A main parking lot is behind the building near the museum’s entrance. We followed the road in front of the building down to additional parking and an area that had once been a playground for Warther’s children.

The Playground

Warther then converted the hillside and lower millstream area, referred to as “Calico Ditch,” into a playground for his children and their friends.

Kids from all around town came to play. There was a cave in the wall and a swing hung from a high branch of a huge Elm tree in such a way that, for a kid swinging on the hillside, it felt like flying.

The hillside is park-like . . . quiet, shaded, and restful . . . with dappled sunlight peeking through the old trees.

The lower parking lot is adjacent to the grassy area where Warther built the playground for his children. Through the trees, you can see the Warther home at the top of the hill.

It’s only appropriate that the playground area should have a restored telegraph office, B&O caboose, and a narrow gauge “yard” engine where small children can play and pretend to drive a train.

We missed it, but it’s worth seeing

Though most of the original playground is gone, a cave Warther built for his children to use as a playhouse still exists. It’s located in the wall in the hillside under the workshop and Swiss flower garden.

From the lower parking level there is nowhere to go, but up. A warm welcome from the Warther family greets you.

On the way up, you can stand on a certain stone to see Ernest Warther’s original workshop framed between the trunks of two trees. It’s a photo op with a posted sign marking the spot. Stone steps continue up the terraced hillside to the house and gardens.

At the top of the hill, looking down on the playground.

The Warther Home

The home where Ernest and Frieda Warther lived for 63 years and raised five children sits at the top of the hill on a narrow lot at the very dead end of a residential street. Warther began building the two-story house himself in 1910 using locally-made burned bricks. It took him two years to finish.

Rear entrance of the Warther home with Freida Warther’s vine-covered Button House [on left], and the grape arbor and Swiss flower gardens [on right]. (Photo: Warther Museum)

We missed it, but it’s worth seeing

We had arrived late in the afternoon and didn’t have time to step inside, but the house is open for public viewing and its rooms have been restored to their former glory.

Imagine sitting on the porch swing in the summertime. Bliss. (Photo: Warther Museum)

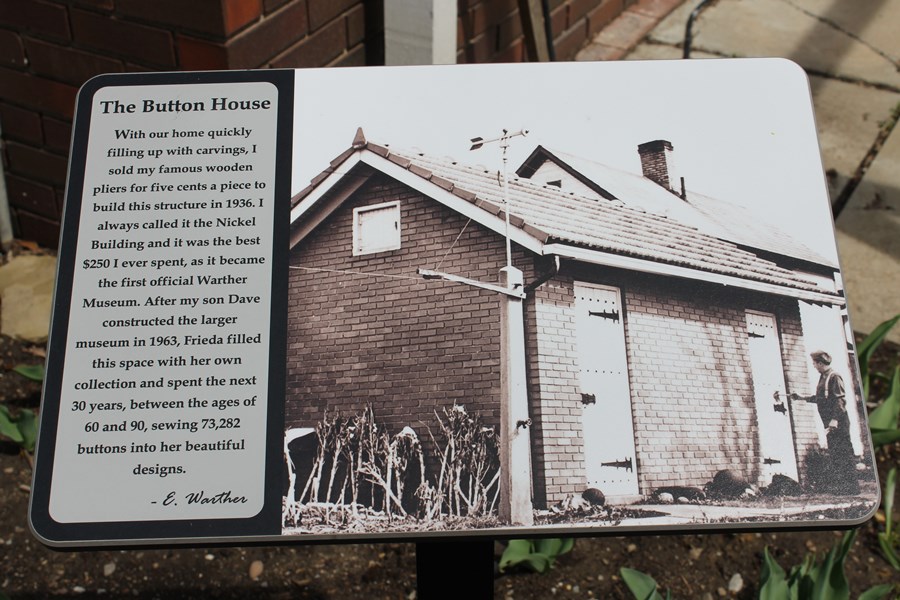

The Button House

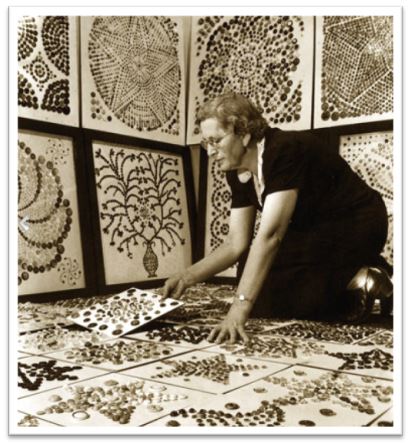

Freida Warther’s Button House is a small brick building directly behind the Warther’s home. A totally unexpected surprise. It appears that Freida, like her husband, was also a gifted artist.

Sign at the Button House tells how, when, and why it was built. There are signs everywhere that explain what you are seeing. The signs make for an interesting and informative self-guided tour.

If you love mandalas, you will love this!

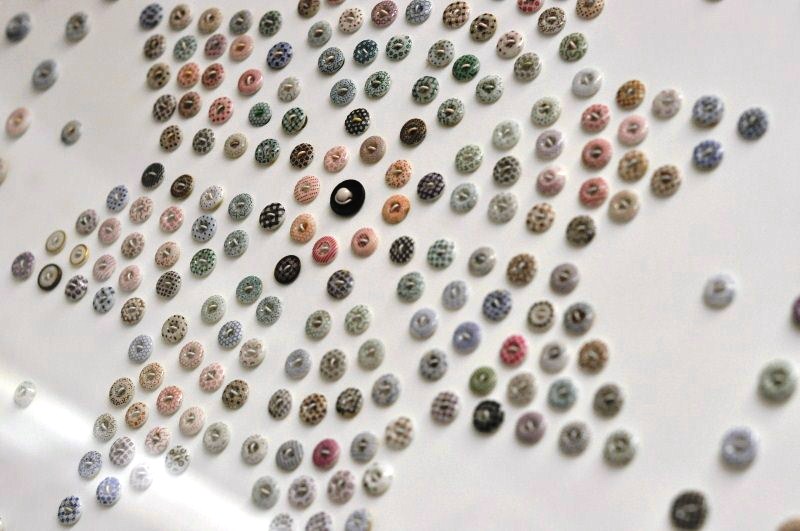

Walls and ceiling of the small building are completely covered with quilt patterns, mandalas, and other unique designs Freida created using buttons from her life-long collection.

Inside Freida Warther’s Button House.

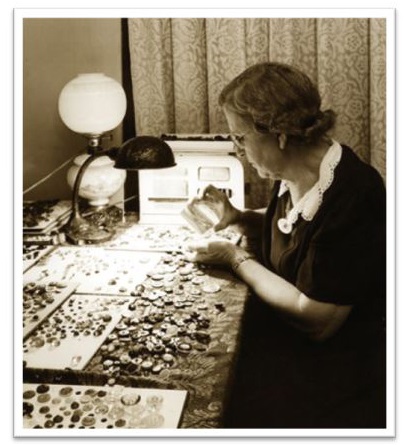

Freida began collecting buttons when she was ten years old and amassed over 100,000 in her lifetime. She had just about every type of button including hand-painted ceramic, Goodyear rubber, pearl, brass military, celluloid, calico, and even a button from Mrs. Lincoln’s Inaugural dress.

After her children were grown, Freida laid the buttons out in traditional quilt patterns and her own unique designs. She then sewed each button onto the panels by hand.

The collection is visually stunning and impressive. Over 73,000 buttons are on display. Freida arranged the buttons by color, shape, and size in elaborate patterns. It is astonishing just how intricate the patterns are.

Tools she used are also on display. Nothing fancy here . . . which makes Freida’s work all the more amazing.

Each button was sewn on by hand. (Photo: The Little Red Hen)

The Grape Arbor and Gardens

Across from the Button House and nestled in a quiet corner of the flower garden is a grape arbor. Ernest Warther built it in 1916.

The Button House, the Warther home, grape arbor, and garden . . . lovely. (Photo: Living Our Dream)

The arbor’s lush Concord grapevine is over 90 years old and provides

a beautiful canopy for visitors. (Photo: Warther Museum)

In addition to collecting buttons, Freida was an avid gardener who loved to make arrangements with the flowers she grew. She designed her gardens in traditional Swiss raised beds and converted the subsoil into topsoil using her own organic gardening techniques. The gardens are still being maintained by the Warther family in the same manner.

Gardens at the top of the hill overlooking the lower playground and parking area. (Photo: Warther Museum)

The Workshop

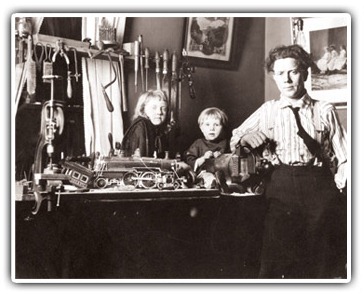

Built in 1912, Warther’s workshop is located directly down the walkway from his home. It is a small, unassuming white building—just 8-feet by 10-feet—with green trim and a brick chimney. A side porch overlooks the terraced hillside and grassy area below where the playground once was.

The original workshop is now adjacent to the Warther Museum. (Photo: Living Our Dream)

Warther hand-carved everything—he never used power tools of any kind. When he couldn’t find a knife to suit his carving needs, he made his own. When his carving knives would not stay sharp, he invented one with interchangeable blades. Eventually, his knife making evolved into Warther Cutlery, which is the family’s current business.

Ernest Warther with his children in his workshop.

(Photo: Warther Museum)

Warther’s workshop, just as he left it . . . with his many chisels, carving knives, and an unfinished locomotive sitting on his workbench. (Photo: Ohio Festivals)

Ernest and Freida spent many Sunday afternoons taking long walks looking for American Indian arrowheads and artifacts. They had ultimately amassed over 5,000 pieces, most of which were found in Ohio. On display in the workshop are many of the arrowheads Warther collected while hiking with Freida. They are arranged in patterns much the same as Freida’s buttons.

Framed displays of the Warther arrowhead collection cover walls and ceiling in the original workshop.

(Photo: Ohio Festivals)

Warther Museum

In 1963, Warther’s son Dave built a building adjoining the original workshop to house his father’s carvings. The building now serves as a lobby for the actual museum.

Entrance to the Warther Museum.

With the opening of the new museum, Warther was honored with a parade and program at Crater Stadium where he was presented with a bronze bust of himself. The bust, as well as a case of arrowheads from his collection, are on display in the museum lobby.

The first section of the museum is devoted to Warther’s early years. On display are photographs, memorabilia, and countless varieties and sizes of the “signature” pliers Warther made.

Ernest Warther carved about 750,000 wooden pliers in his lifetime.

After learning how to carve a working pair of pliers out of a single block of wood with just ten simple cuts, Warther carved pliers in his free time out of everything—he even carved a working pair of pliers from matchsticks!

After learning how to carve a working pair of pliers out of a single block of wood with just ten simple cuts, Warther carved pliers in his free time out of everything—he even carved a working pair of pliers from matchsticks!

Family trees

The Pliers Tree

The Pliers Tree From June 24 to August 28, 1913, Warther worked on the largest “family” tree he would ever make. Known as the Pliers Tree, the tree was carved from one single block of wood and has 511 interconnected, working pliers made with 31,000 cuts. The entire tree can be folded back into its original block of wood. The Pliers Tree was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. Professors from Case Western University studied it and declared that “one would have to have an advanced mathematical education to be able to design a block of wood of the correct shape to begin such a project.” Warther, who only went as far as the second grade, replied that he was glad he was told this after he made the tree and not before.

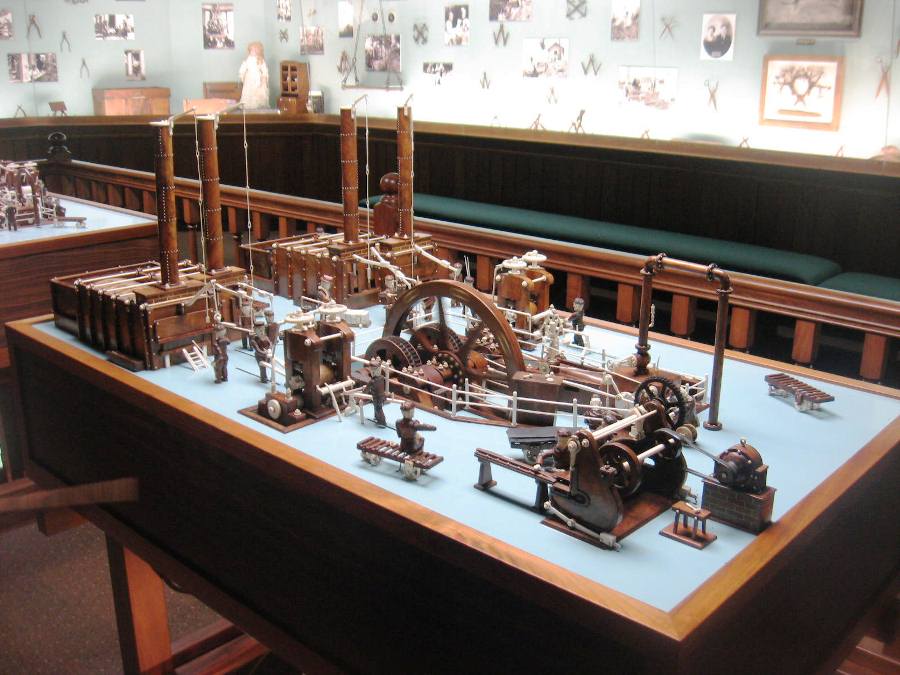

Mechanical model of the local steel mill where Warther worked. (Photo: Steve Brown)

Carved out of walnut and ivory, the model accurately depicts the daily workings of the mill in detail along with its quirkier side, including a sleeping worker, an irate foreman, and a drunken employee hiding in the corner bending his elbow to covertly down a pint of whiskey.

Unbelievable! Though he only had a second-grade education, Warther was able to engineer rotational motion into linear motion, making the various carved figures of his mill move. The complex circular and linear motions are all driven by one sewing machine motor, hooked up to a dizzying array of pulleys and gears on the underside of the display table to control the movement and speed of each figure.

The Big Four Atlantic was carved in 1920. Warther’s masterful sense of scale and proportion are clearly evident. Because they were carved from self-oiling South American wood, all train locomotives and cars still operate.

The collection starts with Hero’s Engine from 250 BC and ends with the Union Pacific Big Boy Locomotive of 1941.

There are 64 engines in the collection, many of them with thousands of delicate interconnected moving parts.

Warther’s first fifteen steam engines were carved from bone and walnut. In 1923, he was able to purchase ivory.

In 1933, Warther completed his finest work, the Great Northern Locomotive. The engine has 7,752 individually carved pieces with a multitude of lines and rivets—each one an exact replica of the real thing—and a “goat” logo in ivory surrounded by mother of pearl. Warther’s own handwriting, inlaid in the base, is hand-carved ivory.

When railroads converted from steam to diesel power, Warther vowed he would never carve a diesel engine if he lived to be 1000. He retired for four years and, at 72, began carving his next great work, “Great Events in American Railroad History.”

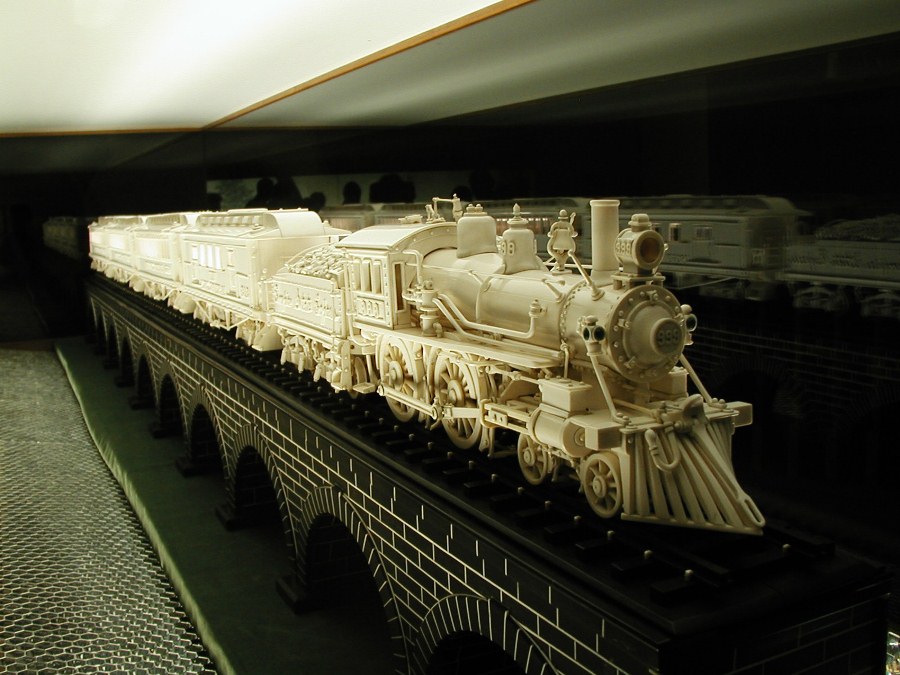

The Empire State Express, and the “stone” arched bridge the train sits on, [above and below] is stunning. At 8-foot long, the it is the largest working ivory carving in the world. The train is carved entirely of ivory . . . and the bridge is made from blocks of ebony with inlaid ivory “mortar.”

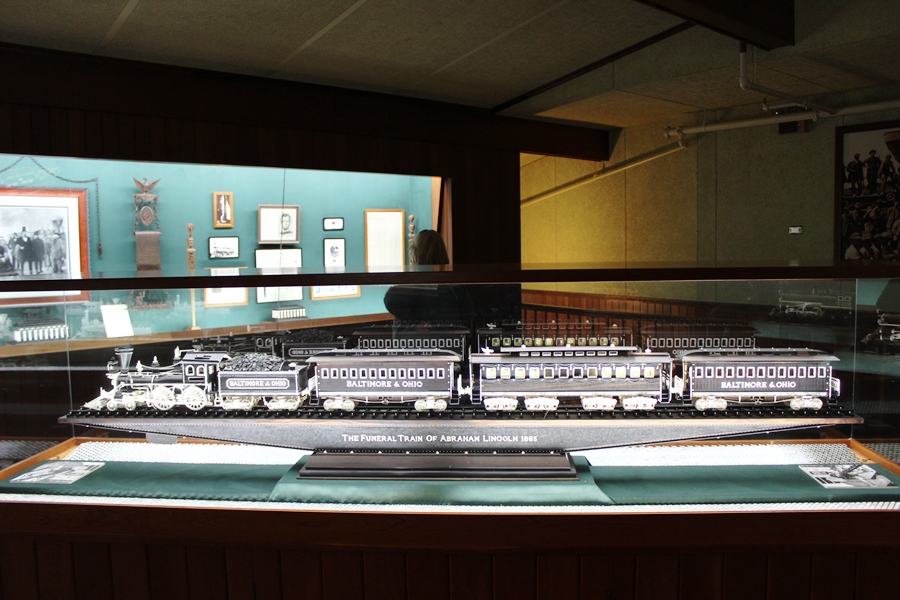

Carvings for the “Great Events in American Railroad History” include the 8-foot long Empire State Express [above], a solid ivory representation of the driving of the golden spike on the transcontinental railroad, and Lincoln’s funeral train [below] which was completed on April 14, 1965—the 100th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination. Warther was 80 years old at the time.

The Lincoln funeral train was carved from ebony and ivory with mother of pearl accents at the bottom of each car. Eyetooth of hippopotamus, the finest grade of ivory, was used. A miniature carving of Lincoln’s body rests in a casket in the center car.

Exhibits at the Warther Museum.

The Union Pacific “Big Boy” locomotive, the largest and last of the steamers, was carved from a single walnut tree stump found in Charm, Ohio. Warther began carving the engine on January 13, 1953 and finished on his 68th birthday, October 30. 1953.

The Lincoln Cane

Warther carved the Lincoln cane while sitting in front of the fireplace during a snow storm. He finished it in 16 hours over four evenings. He then invited people to try to touch the inner-most ball—yes, there is a hand-carved ball inside the cane—with their finger. He told them if they could touch it, he would give them the cane. Visitors brought in infants to try, but no one could do it.

Chess set of ebony, ivory, and pearl Warther hand-carved for comedian Henry Morgan, who helped get Warther on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1965.

IMHO, Ernest “Mooney” Warther was a genius. His talent, time management, and goal setting skills were exceptional . . . and he could pin-point to the day when he would finish carving one of his engines. He woke up every day at 2AM, carved until 5AM, had breakfast with his family, worked a full day (first at a steel mill, then making kitchen cutlery for a living), played with his children after school (and later his grandchildren), had dinner, carved for two more hours, slept . . . and, then, would start it all over again. He did this virtually every day of his life until he died in 1979 at the age of 84. He was driven and disciplined . . . and still had time to make a living, raise a family, travel, and enjoy life, family, and friends to the fullest.

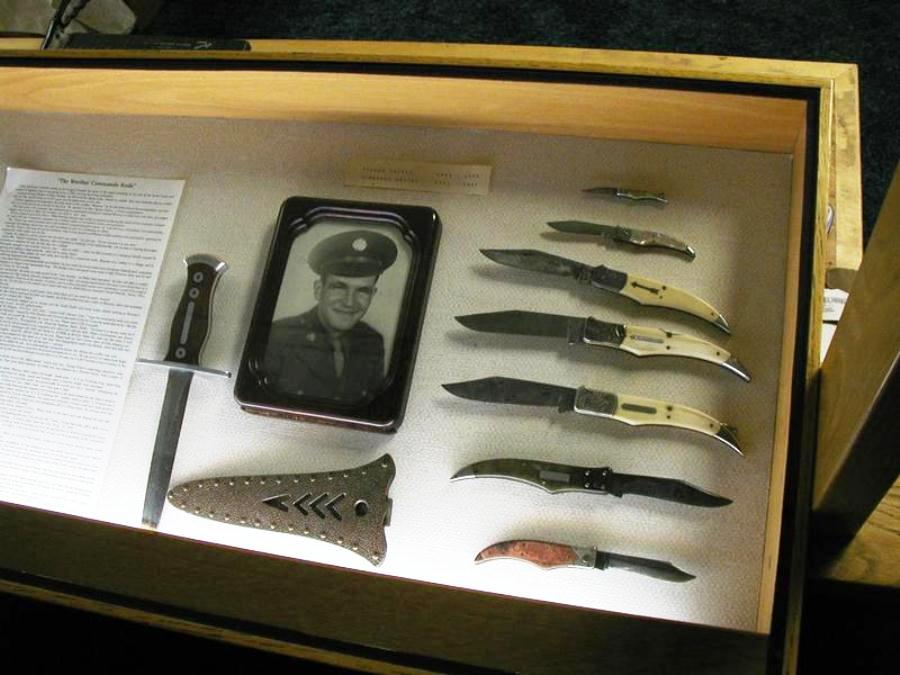

During World War II, Warther stopped carving to make hand-forged Commando knives for local servicemen. He didn’t believe in war, but felt every serviceman should have the best knife possible.

Warther hand-forged Commando knives for local servicemen during World War II.

A giant Warther knife with the signature

fine swirl design on the blade.

Each knife he made was personalized with the serviceman’s name stamped into a brass plate in a cocobolo handle. Each also included a sheath of copper and stainless steel. When Warther heard that the war had ended, he put down the knife he was working on and never finished it. That knife remains in the museum today unfinished.

Just before leaving the building, you can view the factory for Warther Cutlery, the family business started in 1902, and stop at the delightful gift shop that carries the entire line of handcrafted cutlery as well as other high quality items.

The Warther Museum is loaded with model train and other carvings, arrowheads, knives, photographs, and other memorabilia that paint a vibrant history of an extraordinary man, his life, and family. There is a small admission fee for the hour long guided tour—it’s well-worth every penny.

If you ever have the chance to go, prepare to be amazed!

Copyright © 2011 Patricia Petro/Tom Schmidt. All rights reserved.

Some photos posted were found online. Links to the source sites are provided below. I encourage you to visit these sites to read what others have to say about Ernest Warther and the Warther Museum.

Craftsmanship Museum | Living Our Dream | Ohio Festivals | Olivia and Fred Harrington | Roadside America | Steve Brown | Teleoscope | The Little Red Hen

Share Your Thoughts